The Silence Before the Attack: The role of passive OSINT reconnaissance in pentesting

A single domain, a few skilled analysts and passive OSINT reconnaissance can already be enough to outline an organisation’s digital exposure. We are not talking about exploits or active attacks, but about reconnaissance: the quiet yet critical phase in which only publicly available information is analysed.

The real question is not whether this happens, but who does it first: an attacker, or a professional working with defensive intent.

OSINT – Open Source Intelligence, applied systematically

OSINT (Open Source Intelligence) is an information-gathering methodology based exclusively on publicly accessible sources. These include domain registration records, DNS information, certificate logs, search engine indexes, archived websites, and data published on social and professional platforms.

It is important to stress that OSINT is not illegal data collection. It does not involve intrusion or unauthorised access, but rather the collection, correlation and interpretation of information that is already public.

When we talk about information security, attention often jumps immediately to exploits and active attacks. In practice, however, the first step is almost always reconnaissance – and in most cases, this step is entirely lawful.

Why is passive reconnaissance critical?

During passive reconnaissance, there is no direct interaction with the target system. No ports are scanned, no packets are sent, no authentication attempts are made. The analysis relies solely on data collected and published by third parties.

From an engineering perspective, this is particularly important: the target system has no visibility that reconnaissance is taking place. Yet the resulting picture of infrastructure, technology choices and operational patterns can be remarkably detailed.

Using a simple analogy: instead of entering a house, we observe it from the street. We note routines, movements and visible relationships. This alone is not an attack – but it can be a highly effective preparation phase.

Active vs. passive reconnaissance

Active reconnaissance involves direct communication with the target system. Port scanning, service version enumeration and endpoint probing are effective techniques, but they are logged and may raise legal or compliance concerns.

Passive reconnaissance, by contrast, relies on open databases, search engines, and archives originally created for business, research, or security purposes. These are not attack tools, yet they are perfectly suited to mapping an organisation’s digital presence.

This is the phase that remains invisible to the target, while still shaping the direction of a later attack or a professional penetration test.

The domain is a starting point for reconnaissance

One of the most stable entry points for analysing an external attack surface is the domain name. Domain registration data does not reveal vulnerabilities on its own, but it provides context: how long the digital identity has existed, which providers are involved, and how consciously it is managed.

A domain that has existed for decades almost certainly carries technological legacy. Migrated systems, forgotten subsystems and residual services are common in such environments and often become visible during reconnaissance.

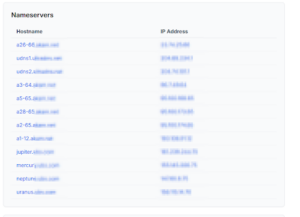

The number and type of name servers, along with their distribution, provide insight into the complexity of the DNS architecture. These elements are not risks by themselves, but they guide further OSINT analysis.

Domain registration information and historical data from open sources

The name servers belonging to the domain and their public IP addresses

DNS, caches and passive DNS databases

The Domain Name System is inherently public. When an IP address is resolved for a domain, the response is cached by resolvers, providers and security systems. These observations form the basis of passive DNS databases.

Publicly Available DNS Records and IP Address Associations

Such systems do not perform active queries; instead, they archive previously observed DNS traffic. This makes it possible to reconstruct historical IP assignments, subdomains and infrastructure changes over time.

From a security perspective, this data often highlights systems that an organisation has forgotten about, but which may still be reachable in some form.

Certificates and Certificate Transparency

TLS certificates are governed by the Certificate Transparency framework. Every issued certificate must be logged in public, append-only logs that are accessible to anyone.

Analysing these logs frequently reveals not only the primary domain, but also numerous subdomains listed in certificate SAN fields. Development, testing or internal hostnames appear regularly. This is not a flaw, but a natural side effect of modern certificate management.

Certificates and Subdomains Observed in Certificate Transparency Logs

Google as a passive reconnaissance tool

One of the most powerful yet frequently underestimated tools in passive reconnaissance is the Google search engine. Not because it “hacks” anything, but because it reflects what has been made publicly accessible on the web sometimes unintentionally. Search engines index not only HTML pages, but also documents, archives, configuration files, and, in many cases, files that were never meant to be publicly exposed.

In this case, a precompiled and commonly used search query set was applied, specifically targeting exposures that frequently occur in corporate environments.

Searches for publicly accessible documents are designed to identify which offices or structured files are available under a given domain. These are typically internal materials, exported reports, or past presentations that may contain both metadata and meaningful content.

| site:www.xxx.com ext:doc | ext:docx | ext:odt | ext:rtf | ext:sxw | ext:psw | ext:ppt | ext:pptx | ext:pps | ext:csv |

Searches targeting indexed content primarily highlight cases where a web server allows directory listing and the search engine has indexed those listings.

| site:www.xxx.com intitle:index.of |

When searching for configuration files, filtering is typically applied to file types that may contain application- or system-level settings. While these files rarely constitute an immediate vulnerability on their own, they can reveal valuable information about technologies, environments, and internal structure.

| site:www.xxx.com ext:xml | ext:conf | ext:cnf | ext:reg | ext:inf | ext:rdp | ext:cfg | ext:txt | ext:ora | ext:ini | ext:env |

A similar approach is used when searching for database files and backup artefacts. Such files are often uploaded to a web server temporarily and later forgotten, while search engines may retain indexed references to them for extended periods.

| site:www.xxx.com ext:sql | ext:dbf | ext:mdb

site:www.xxx.com ext:log site:www.xxx.com ext:bkf | ext:bkp | ext:bak | ext:old | ext:backup |

Searches related to login and registration interfaces are not intended to bypass authentication, but rather to identify where authentication endpoints are located and what URL patterns are exposed under the domain.

| site:www.xxx.com inurl:login | inurl:signin | intitle:Login | intitle:”sign in” | inurl:auth

site:www.xxx.com inurl:signup | inurl:register | intitle:Signup |

Identifying error messages is particularly important, as they often reveal implementation details, database types, or backend logic without requiring active testing.

| site:www.xxx.com intext:”sql syntax near” | intext:”syntax error has occurred” | intext:”incorrect syntax near” | intext:”unexpected end of SQL command” | intext:”Warning: mysql_connect()” | intext:”Warning: mysql_query()” | intext:”Warning: pg_connect()”

site:www.xxx.com “PHP Parse error” | “PHP Warning” | “PHP Error” |

The investigation of leaked code snippets and configuration data also extends to third-party platforms. Paste sites, code repositories, and technical forums often contain examples, bug reports, or temporary solutions that may include domain names, API endpoints, or internal details.

| site:pastebin.com | site:paste2.org | site:pastehtml.com | site:slexy.org | site:snipplr.com | site:snipt.net | site:textsnip.com | site:bitpaste.app | site:justpaste.it | site:heypasteit.com | site:hastebin.com | site:dpaste.org | site:dpaste.com | site:codepad.org | site:jsitor.com | site:codepen.io | site:jsfiddle.net | site:dotnetfiddle.net | site:phpfiddle.org | site:ide.geeksforgeeks.org | site:repl.it | site:ideone.com | site:paste.debian.net | site:paste.org | site:paste.org.ru | site:codebeautify.org | site:codeshare.io | site:trello.com www.xxx.com

site:github.com | site:gitlab.com “www.xxx.com” site:stackoverflow.com “www.xxx.com” |

Finally, subdomain and sub-subdomain searches allow hostnames already known to search engines to be identified in a fully passive manner.

| site:*.www.xxx.com

site:*.*.www.xxx.com |

These searches do not guarantee results, but they do provide insight into what the outside world can already see about an organisation.

The human factor in OSINT

Passive reconnaissance does not stop at infrastructure. Once the technological landscape and organisational scale are visible, examining the human layer becomes the next logical step.

Public professional platforms such as LinkedIn can reveal an organisation’s structure, roles, and technology focus. On their own, these details are harmless. Placed in a technical context, however, they can support highly targeted attack scenarios.

Public Professional Network Data as the Foundation for Later Targeted Attacks

Public Professional Network Data as the Foundation for Later Targeted Attacks

Shodan: when others have already scanned the internet

Shodan is a search engine that aggregates banner information returned by internet-connected devices. When an analyst uses Shodan, they are not scanning the target system themselves; they are reviewing data collected previously by others.

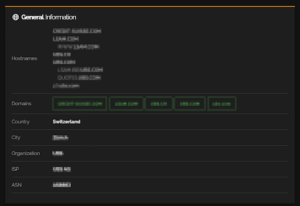

Network and geographic information for a public IP address based on Shodan

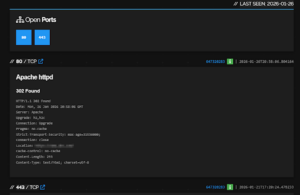

Searching by domain or organisation reveals associated IP addresses, exposed services and historically open ports. These datasets allow further analysis at the level of geography, hosting providers and network structure.

Public service and port information collected by Shodan

Internet Archive and the Wayback Machine

The Internet Archive has been collecting snapshots of websites for decades. A single domain may have tens of thousands of archived versions, sometimes dating back to the mid-1990s.

Website backups in the Internet Archive Wayback Machine

These snapshots enable analysis of how a site has evolved over time. Old administration interfaces, deprecated features or removed content may still be visible. From this, one can infer internal processes, technology decisions, or even data-handling practices.

Summary

The steps outlined above demonstrate how detailed a picture can be built about an organisation using passive OSINT reconnaissance alone. Domain data, DNS history, certificates, search engine indexes, archives and public platforms together form an information set from which experienced analysts can draw precise conclusions.

Because all of this happens without any direct interaction with the target system, passive reconnaissance is not only an attacker technique, but also a critical defensive control point. Organisations that do not know what they expose through the public internet cannot fully understand their external attack surface.

The methods presented here serve as a starting point for professional penetration testing, security awareness programmes and defensive assessments.

If your organisation operates a complex digital environment and processes personal or business-critical data, it is worth understanding what can already be learned about your infrastructure from publicly available sources. If you would like to assess this from a professional, ethical hacking perspective, we invite you to get in touch.